At a recent Bonhams sale in London, a 1972 Patek Philippe gold and lapis lazuli jewellery watch sold for over £28,000, somewhat above its estimate, as befits a classic “buy” item on its way into favour, but not quite peaking. Its mix of mid-century, jet-set glamour and ancient influences reflects a growing passion for hardstone and gold watches over the past few years.

Jewellery Designers re-enter the Golden Age

10th April 2024

The precious metal has enjoyed a return to favour in recent years, with watch and jewellery brands elevating archival designs for a contemporary audience as they re-enter the golden age.

The conservative and industrial watch industry often lags behind jewellery on creative style but this is a rare example of it inspiring jewels. The major return of yellow gold, with or without hardstones and gems, is now sweeping the market at all levels, perhaps as a reaction to the strictures of the pandemic and economic woes. Designer Annoushka Ducas is best-known for coloured stones and antique-style settings but her latest collection is exclusively gold. “I don’t design to trends but this is more a general feeling,” she says. “Maybe the social background is an unconscious need for something timeless, contemporary and flexible, that will work in 10 or 200 years’ time. Yellow gold flatters most skins and ages, but gold is still an investment and needs to work hard.”

Those original timepieces were more jewel than watch, their cases and bracelets handworked in engraved or woven gold, dials often delicate, hand-cut layers of mineral. According to Bonhams’ global head of watches, Jonathan Darracott, the lapis model “would not technically have been unique but Patek probably made 10 at most.” Such styles doubled as bracelets and often had a matching suite of earrings and a necklace. Some had similar cufflinks — men in that peacock era happily wore gemstones and are now returning to them.

At the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, these suites, with their nostalgic, opulent blends of colour and high craft, draw in visitors, and also possibly inspire designers. Brands with a similar heritage such as Piaget, which has always created jewellery alongside watches and has employed its own goldsmiths since the 1960s, or Van Cleef & Arpels in the highest tradition of Parisian jewellery, are mining their own archives for designs to contemporise.

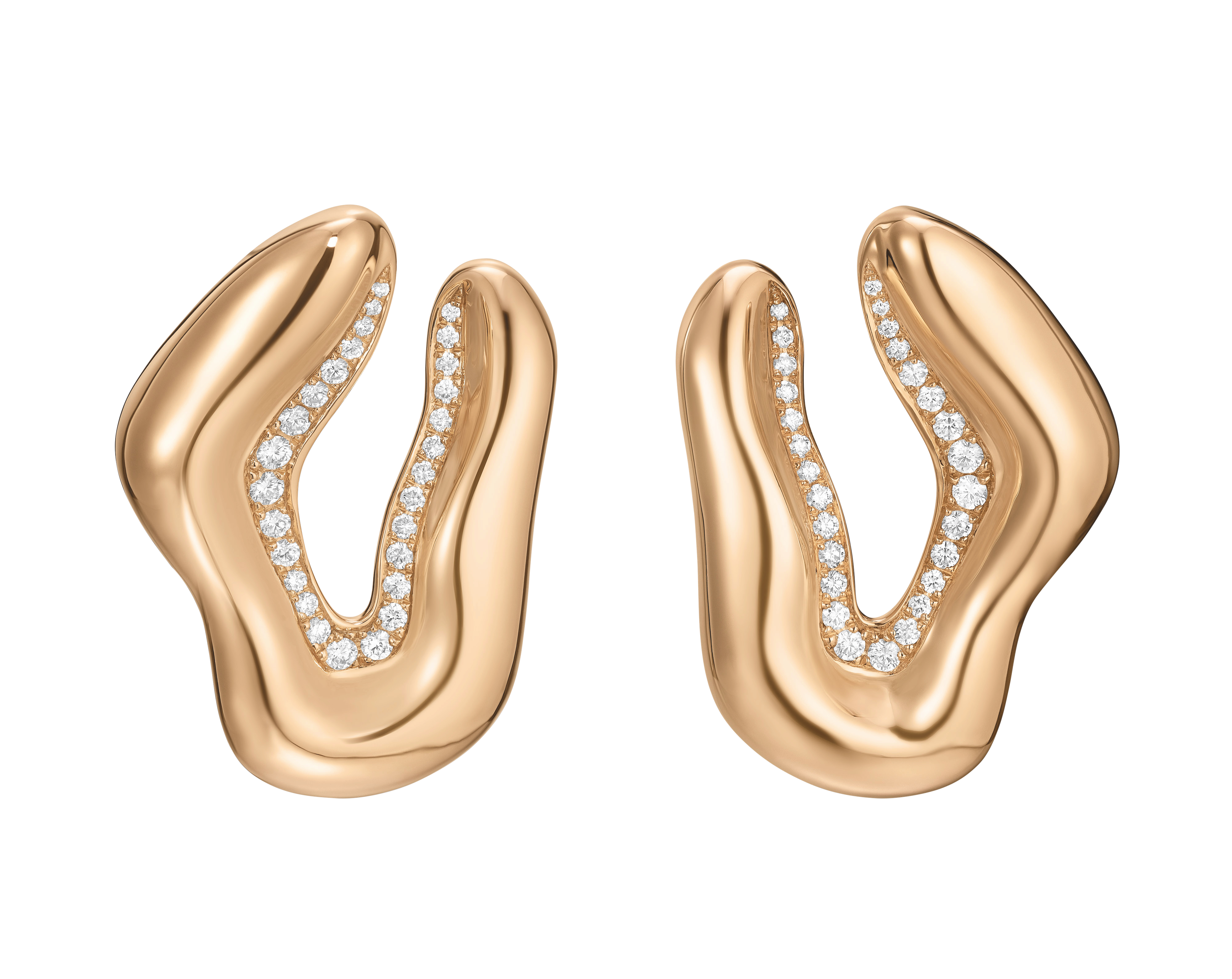

Van Cleef & Arpel’s slightly jokey, sometimes cutesy animal clips brought levity and the finest gold engraving to high jewellery in the 1960s and are still highly sought after. Its 1967 Dishevelled Lion clip, with fine gold dreadlocks and diamonds, emeralds and onyx, is more sweet cartoon than noble beast. This spirit is perfectly replicated in the current revival with its perlé mane, tiger-eye “fur” and loveable expression. Piaget’s Essentia capsule in its new high jewellery collection references the organic, abstract shapes of the 1960s, with freeform links of polished gold and diamonds on earrings, necklaces and a mineral-dialled watch.

Creativity is often circular. The original watches were inspired by jewellers such as Andrew Grima and Gilbert Albert, who designed unique pieces for Omega, and Grima’s love of organic shapes, yellow gold and rough stones is a major jewellery influence. Designers known for other styles are experimenting with gold in new-for-them ways. Bibi van der Velden, associated with slightly gothic, engraved gold animal motifs, captures in metal the ephemeral essence of smoke spirals, or the underwater movement of seaweed, shells and even mermaids. Elizabeth Gage, known for ornate, medieval or Roman-looking rings set with gems and enamel, explores gritty textures and monolithic, irregular shapes, and is guided by the outlines of natural stones.

These organic motifs inspire designers as disparate as Brazilian talent Fernando Jorge, whose effortless ribbed or polished pieces seem impossibly light; Indian designer Ananya Malhotra, whose sophisticated mix of subtle gems, pearls and gold recalls fossil seashells; and Beirut brand L’atelier Nawbar, where sisters and fourth-generation jewellers Dima and Tania Nawbar use delicate fretting and edgings of diamonds or vivid enamel to enhance fluid shapes.

By recreating freeforms, jewellers give unconventional modernity to 1960s style. Suzanne Kalan is celebrating 10 years of her USP: the arrangment of little baguette diamonds at random angles so light dances off them in different directions, like tumbled rock strata. Her original, now re-issued, bracelet also comes in gold baguettes and she has expanded the theme into coloured gem baguettes, including very 1960s emeralds with yellow gold. Designer and V&A curator Emefa Cole is equally fascinated by geology. After her glowing gold, volcanic crater rings comes her excursion into “frozen” molten gold, which resembles dripping lava or stalagmites from a mythical limestone cavern.

Even tiny details can inspire imaginative leaps. Dominic Jones, creative director of the Royal Mint and its 886 jewellery range, subtly references the company’s historic purpose of coin making in his second collection, Tutamen. Earrings with coiled spiral motifs are inspired by the milled edges of coins, and feature the Latin inscription Decus et Tutamen, which appeared on the iconic 1990s £1 coin, stacks of which also inspire graduated disc earrings. “The inscription means ‘an ornament and a safeguard’, and fits what I want for the Royal Mint’s jewellery,” says Jones. “That it should be decorative but also hold its value as an investment.”

Classic jewellery houses have deep archives and can command the best of craft to reinvent past motifs. Cartier’s current headline gold range, Grain de Café (coffee bean), rebelliously ordinary when launched in 1938, is now seen as joyously quirky, unless you have the high jewellery version with rubellite beads and diamonds.

With nearly 250 years of history, Chaumet has seen many gold waves, from an early golden wheat-ears tiara to intricate, mid-century, nature-inspired creations by celebrated maker Pierre Sterlé — and both eras are referenced in current collections. A simple pendant in the latest fine jewellery Liens range is elevated by a dazzling engraved sunburst, while Le Jardin de Chaumet’s unique pieces include wheat in gold and diamonds; engraved, layered gold palm fronds; and abstract leaf shapes set with yellow and white diamonds garlanding a band of multi-cut diamond “stripes”.

Paris has no monopoly on splendid goldsmiths. Italy has its own historic traditions and styles, from Vicenza and Valenza in the north through Florence to Sicily in the deep south. Northern craft peaks in the gauzy metal and gems designs of Buccellati and the bolder gold of Pomellato, which, in the 1960s, took the chain from being a means of suspending a pendant to a substantial piece that included high jewellery versions pavéd with diamonds or coloured gems. The chain has now been elevated everywhere to newly complex levels, including by UK jewellers such as Pragnell, which stacks different chain designs together and uses chain tubing to create 1940s-inspired, industrial-looking rings.

Annoushka’s latest, non-gendered collection Knuckle is based on the eponymous bone, with a striking knot effect between each link. The knot is also the heart of Tiffany’s newest gold collection while Florence-based Gucci returns to its ultimate 1960s symbol, the snaffle, with intricate bracelets, including cuff watches.

Sicilian gold is different, more obviously handworked and textured rather than polished, with motifs that look to the eastern Mediterranean, as evolved from ancient Greek-inspired jewellery by Ilias Lalaounis in the 1970s, which caused a sensation. Massimo Izzo handcarves and engraves one-off pieces, combining fine filigree work with large, unusual stones such as aquamarine slices and Japanese coral, and featuring motifs from sea creatures to the universal sun symbol, in 1970s-style sand-blasted gold. With a shop in Siracusa, he also takes his work to collectors worldwide.

It resonates with the equally soft finish and tactile shapes of Beirut-born Nada Ghazal, whose jewellery is made in the Lebanese capital while she is currently based in Britain. Her home city and its mid-century heritage of sophisticated jewellery design remain her inspiration. “I gravitate to bold, architectural designs, which we handcraft,” she says. “My latest are based on ancient Beirut doorways and arches — symbols leading you somewhere new. They are very sensual. I love working with texture, whether traditionally embossed or with modern techniques like sandblasting or brushing.”

The mid-century version of ancient jewellery also inspires top costume jewellers like Goossens, founded in the 1950s and long-term jeweller to Chanel — which now owns the brand — with its mixes of 24ct gold overlay and dyed rock crystal, or the witty, 1970s-style creations of Sonia Petroff, a Bulgarian aristocrat and original jetsetter whose archive has been revived and updated by her niece-in-law Maria Leoni-Sceti. Not all high jewellery houses have such close links with the last golden age but right now it is where everyone in the industry wants to be.